SCOTTISH MYTHS & CURIOSITIES

When you look at Scotland with a fresh pair of eyes and a rational mind, you can begin to understand how Scotland’s myths and curiosities have emerged. With ever-changing weather, strange land formations, rugged landscape and mystical lochs, you truly feel like you have landed in a magical place. Together with the Scot’s famous savvy storytelling, the legendary tales have been carried down through generations, living on for each visitor to experience like a candle in the wind. Scotland is a land full of superstitions, folklore and legends to encounter.

The people who live in Scotland have grown up with legendary stories, which have amassed since prehistoric times. Scotland’s many visitors are often drawn to the mythical nature of the land and feel a sense of adventure with a supernatural aura of mystery. Often connecting with local people in areas of Scotland, opens up a bond and an internationally renowned sense of belonging to this beautiful country. Scotland’s traditions and culture are juxtaposed with silly stories and beliefs, which over time evolve and blur the understanding between facts and history.

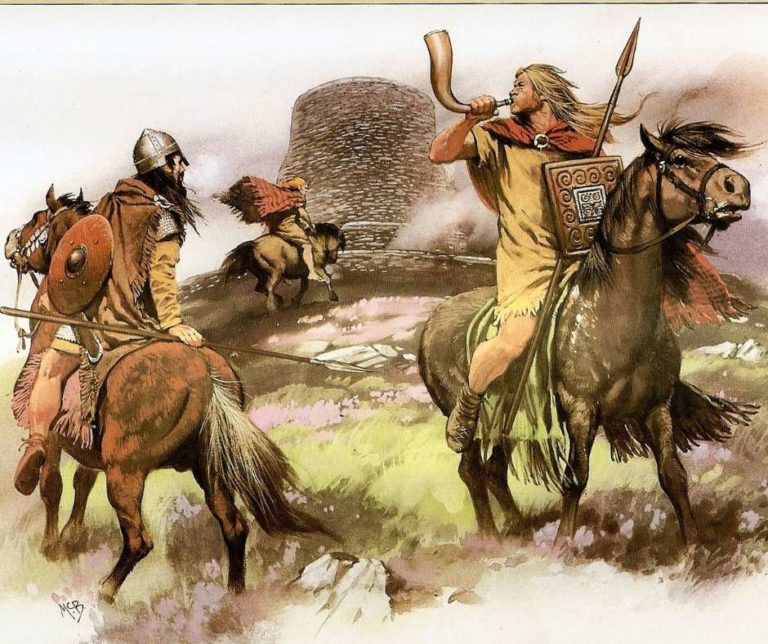

Scotland Origin

The Roman Empire arrived in Scotland in the 1st century, according to recorded history. The province of Britannia reached as far north as the Antonine Wall and to the North of this was Caledonia, which was inhabited by the Picti, whose revolt forced Rome’s legions back to Hadrian’s Wall.

The Gaelic kingdom of Dál Riata was founded on the west coast of Scotland in the 6th century. Although, one legendary myth suggests that this was formed by Irish descendants. The foundations of the story point to Fergus Mor mac Eirc, who supposedly established a new Dál Riata in Argyll because of dynastic competition at home (Foster, 1996:13). They displaced a previous community of settlers there, a process which eventually ended in the takeover of the entire Kingdom in the 9th century, to create the United Kingdom of Alba, which became Scotland.

In truth, this is all just Irish craic, according to archaeologists who researched further during a dig in the 1970s. An excavation at the Royal Fort at Dunadd in Argyll was identified as the inauguration site of some of the earliest Scottish kings but their findings show there was no link with Ireland and no evidence that there was an invasion in the 4th or 5th century. No Irish artefacts were found during this dig but there is evidence collected that the two countries traded often, and many were Gaelic speaking on the West Coast of Scotland.

The origin of this story is thought to have been medieval spin doctors for political purposes, attempting to further the claims to the Scottish throne of descendant Kenneth MacAlpin (King of the Picts). An attempt to re-write history.

However, Irish missionaries did introduce the previously pagan Picts to Celtic Christianity. Following England‘s Gregorian mission, the Pictish king Nechtan chose to abolish most Celtic practices in favour of the Roman rite, restricting Gaelic influence on his kingdom and avoiding war with Anglian Northumbria.

Towards the end of the 8th century, the Viking invasions began, forcing the Picts and Gaels to cease their historic hostility to each other and to unite in the 9th century, forming the Kingdom of Scotland.

Painted Face Highlanders

According to Roman history, Britons often painted themselves with woad, which produced a blueish tint, giving them a wild look in battle.

There is a big conflation with this theory based on the Romans also calling the northern people ‘Picts’ (derived from the Latin equivalent ‘Picti’, meaning ‘painted or tattooed people’.

Therefore, it was a name thought to have been placed on them by the Romans. They could have simply used this term in a derogative manner, as they considered them barbarians.

So maybe the Picts liked to wear war paint, or had elaborate facial tattoos. We can’t prove it, but it’s not a wild historical error to show Roman-era Picts decorated that way. There is no evidence for Pictish influence on 13th century Scottish culture. By the 11th century the Picts had been completely assimilated to Scottish culture, and they left only archaeological remains and a few hard-to-understand documents. There is absolutely no historical evidence that 13th century Scotsmen painted their faces.

Wearing underwear under your kilt

The kilt is an iconic Scottish garment, but it also comes with a number of misconceptions. Most of all there is the assumption that a male kilt wearer is doing so without undergarments, as this is how it should be ‘traditionally’ worn. This myth is so widespread that people worldwide believe that there is a written rule somewhere in Scottish law that in order to be authentic, Scots should go without their pants to be authentic.

There is some link to the Highland Regiments of the British Army, who supposedly required that soldiers in kilts not wear underwear. This was deemed as a form of sexual harassment with officers inspecting that their men were going regimental during patrols.

In truth, in the 16th century, when kilts became a standard garment for Scots, very few people sported undergarments. This was because it was only aristocrats and royalty who owned these items, but farmers and hunters of Scots clans didn’t and possibly couldn’t afford to. There is no special significance attached to it or a particularly good reason behind it. Perhaps, for other cultures, it’s the shock of seeing a man wearing a skirt/dress and the increased concern that he may be naked underneath it too. Shock and awe lead to storytelling over centuries.

David Hume's Toe of Good Fortune

David Hume was one of the world’s most celebrate philosophers and as such he was commemorated with a statue on the Royal Mile, which was unveiled in 1997.

Apparently, the sculptor decided to make Hume’s big toe poke over the edge of the plinth to entice people to touch it. This has led to the bizarre tradition of touching his toe for good luck and Edinburgh students particularly do this before their exams, along with hordes of tourists, which turned the toe a shiny golden colour.

It is ironic that one of Hume’s famous theories was that there is no direct link between cause and effect between two unrelated events so he would have considered all this a lot of nonsense. This famous Edinburgh landmark portrays Hume as an ancient Greek philosopher. While he was neither ancient nor Greek, Hume was also an influential historian, economist, and writer who lived in the Scottish capital from 1711 to 1776.

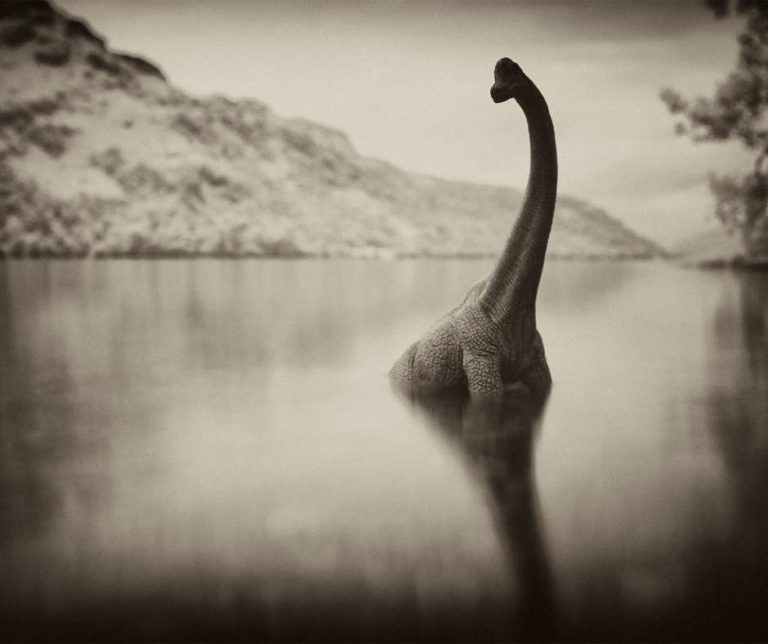

Nessie

Nessie is the loving name given to the ‘water beast’, otherwise known as the Loch Ness Monster. This was first chronicled in the 5th century by St Columba but came to the world’s attention in 1933. A Scottish newspaper reported that a London visitor saw a prehistoric, dragon-like animal bobbing in Loch Ness. In the same year, the famous first photo was published.

On first utterance of this beast, you may easily dismiss it as nonsense. However, when you consider that Loch Ness is the second deepest body of water in Scotland and contains more fresh water than all the lakes in England and Wales, it seems like there’s actually a lot of room for something large to live there and survive.

There is common speculation that Nessie descended from a species of dinosaur, known as a plesiosaur, which is a marine reptile that swam in water and has actually been extinct for 65 million years. At present, no plesiosaur bones have been found in Loch Ness and despite their being over 22 tons of fish in Loch Ness, this is still nowhere near enough to feed a giant breeding plesiosaur.

Clan Tartans

Another iconic Scottish tradition in the fashion industry is tartan and its links to history of clans in Scotland. However, it is a little unclear as to its origins and definition. There is evidence that Celtic people of the so-called Dark Ages and through to pre-history, wore woven cloth of a counter-check design.

These materials would have been made available locally and produced in methods handed down within small family communities. Therefore, it is not inconceivable that local or tribal differences would have existed. After the battle of Culloden in 1746 Scottish Highland attire was banned by law, and the Gaelic community of Scotland lost touch with its traditional clothes for at least one generation.

It is doubtful that clan tartans as we now know them would have been identifiable but there would have been clear differences between locality cloth, made by one weaver amongst the local community. There was post-Culloden proscription of tartan, which boosted awareness of clan tartans and created their foundation in history. George IV visited Edinburgh in 1822 and there was a rush amongst many of the chiefs to find or identify their traditional district/clan tartans to protect their heritage.

The Kelpies

According to Scottish folklore, kelpies are horse-like water spirits, which are said to have the strength and endurance of 100 horses.

They are shapeshifting, supernatural, mythical beasts, which are rumoured to live in Loch Coruisk, a freshwater loch at the foot of the Black Cuillin range. This lake in the Isle of Skye has been the subject of many Scottish writers and painters and is very popular with tourists. The Kelpies are said to haunt lochs and apparently appear as victims, enticing people to ride them before taking them down to a watery grave.

Likewise, you can’t miss the giant steel horse heads of The Kelpies, just off the M9 motorway near Falkirk. They are located in the park at Helix, a great photo opportunity and are nearly one hundred feet high over the Forth & Clyde Canal.

The largest pair of equine sculptures in the world!

Scottish Mythical Creatures

Scotland isn’t short of mythical creatures with many gracing folklore tales of old.

- Wulver – This is a werewolf from Shetland, which doesn’t fit the typical image of a terrifying werewolf. The Scottish Wulver has the body of a man with a wolf’s head and was said to leave fish on the windowsills of poor families. It was seen as a kind-hearted, generous soul, known to help some of the most unfortunate people in the country.

- Blue men of Minch – These are mermaid-like in their appearance and historical recordings of the creatures say that they lived in underwater caves. The Blue Men of Minch are meant to lure sailors to their deaths in rough seas. Apparently they can only be beaten by making sure the last word is achieved in a rhyming duel. Captains with sharp tongues survived!

- Bean-Nighe – She was a ‘washer woman’, a Scottish fairy seen as an omen of death. A cousin of the banshee in Irish folktales, this creature heralded death. You would find her washing the clothes of those who are about to die, and she would scream before someone was about to die. More often than not these people heard the wail and died of fright.

Wallace fell in love

We are all aware of the warrior spirit of William Wallace and Mel Gibson’s portrayal of him in Braveheart. Scenes from the movie show Wallace’s lady love and her tragic end in the hands of the English. The story goes that he fell in love with a lady called Murron and secretly weds her. Apparently he had no intention of fighting the English or freeing his country until she is killed. Wallace then takes revenge on the Sheriff who slashed her throat by doing the same to him.

The supposed wife was killed in Lanark and Wallace gathered a bunch of men and wreaked havoc on the Sheriff and the English guards. William Wallace was already an outlaw against the English and was opposed to English rule from the very beginning, refusing to sign the Ragman Roll.

William Wallace Sword

The Wallace clan were proud of their archery skills and took pride in using a bow and arrow. However, it is likely that swords were used in battle by Wallace. The Wallace Monument in Stirling, inaugurated in 1869, displays a 163 cm sword, which allegedly belonged to Wallace.

It has been discovered that the Wallace Sword is made of different metals from different weapons, the oldest dating from the 13th century. No record prior to the 16th century mentions the Wallace Sword. Until 1505, when King James IV of Scotland paid to provide the sword with a new hilt, plummet, and scabbard.

Upon close inspection, the sword may be made up from pieces of different swords fitted together. Part of this could have come from a late-13th-century sword. It is the typical two handles but the blade appears to be made of 3 separate pieces hammer welded together.

Haggis wild creature

A well-known Scottish delicacy, haggis is an iconic Scottish dish of sheep’s stomach, stuffed with spiced innards and oatmeal. However, one humorous theory is that the haggis is actually sourced from the wild haggis – a creature with four legs and a shaggy mane.

The legend of the wild haggis is known as an unbalanced beast whose legs are of unequal length, enabling is to lop up steep Scottish hillsides with ease.

Of course, this fuzzy and fascinating wild haggis is not real. Instead, it belongs to the fake-animal pantheon that includes jackalopes and drops bears: a creature of tall tales trotted out to test the credulity of tourists.

The legend of the water under the Sligachan Bridge

Legend has It if you stick your face in the water under the Old Sligachan Bridge for 7 seconds and let It dry off naturally, you’ll be granted eternal beauty. There was the greatest female warrior on Skye named Scáthach.

One day, Ireland’s favourite warrior, Cú Chulainn, travelled to Skye to fight Scáthach and the battle raged on for weeks and weeks. Scáthach’s daughter was tired and worried about all the fighting and for her mother, so she ran to the Sligachan River with her eyes filled with tears, begging for the fight to stop.

She didn’t know that the water is a gateway between the faerie world and ours, and as such the faeries heard her plead. They instructed her to stick her face in the water for 7 seconds, and she’ll have her solution. Then, she ventured around Skye gathering the loveliest herbs, meats and any item of deliciousness that the land produced to prepare the perfect meal.

The smell of the meal was so intense that Cú Chulainn and Scáthach quickly got a whiff of the meal and decided to take a break and enjoy a feast back at Scáthach’s home. The feast marked the end of the battle, just as her daughter wished.

Being a guest, Cú Chulainn was compelled not to harm the host; you can’t fight someone who has hosted you, ever. That was the end of the battle; the two warriors made a truce. The faeries will grant anyone who sticks their face in Sligachan River eternal beauty.